Evaluation of plain language decision writing

1 — Executive summary

The ability of a client before the Social Security Tribunal (SST) to read and understand the basis for the decision on their appeal is fundamental to accessing justice. Since 2017, the SST has provided training, tools and encouragement to its members to write decisions in plain language. The purpose of this evaluation is to determine the effectiveness of the SST’s various supports to members to write decisions that read at a level accessible to lay readers. To determine decision readability, the evaluation collected feedback from self-represented claimants, third-party experts in plain language legal communications, and members themselves.

Members universally expressed positive feedback about the usefulness of the training they received in decision-writing by established experts from both legal and non-legal communities. Future training would be welcome especially from different sources. Members also confirm they actively use the SST’s decision templates and customize them for unique appeals. Members would welcome additional templates covering more appeal types. Other supports are widely used although to varying degrees, reflecting the individualized approach that each member brings to decision-writing. These supports include the SST’s style guide and peer review. Members cite the lack of time as a key obstacle to giving more attention to plain language writing.

A post-decision survey yields client perspectives in combination with personal and appeal-specific characteristics. Survey results show that readability is strongly correlated with a claimant’s educational attainment but other factors are also connected, including the outcome of one’s appeal, language of the decision, and the claimant’s level of language fluency. Overall, clients with higher education struggle least with their decision, and English readers with high school education struggle most. When the outcome is in their favour, claimants rate readability higher. Open-ended comments from successful and unsuccessful claimants suggest changes that would make decisions easier to read, such as making the result easier to find and grasp, and explaining next steps.

The evaluation enlisted third party experts to assess a sample of decisions for their content, structure and style. This text analysis found that the majority of decisions: clearly state the result up front; provide a succinct background of the appeal; explain the applicable law in plain language; write in point-first; and make deliberate efforts to limit jargon, acronyms, and passive voice. Areas for improvement include: better use of headings and sub-level headings, clearer articulation of the issues to be decided, and shorter sentences.

The evaluation concludes with 7 recommendations covering formatting and stylistic suggestions, comprehensive access to member resources, and use of exemplary decisions for training purposes.

2 — Background

The law requires the Social Security Tribunal (SST) to explain to claimants and other parties in writing the reasons for its decisions. Writing decisions in plain language is an important part of helping people access justice. Since 2017, the SST has provided its members with training, tools and encouragement to write decisions in plain language. The decisions that members make have the power to affect people greatly, both financially and emotionally. Those decisions need to be clear and understandable so that the people affected trust that their case was heard and judged fairly.

This evaluation aims to assess how readable SST decisions are from the perspective of their targeted readership – parties1 appearing before the SST – by understanding the unique challenges they face when reading and comprehending their decision. We also invited neutral, third-party experts in plain language legal communications to assess our decisions and give their feedback. Finally, through interviews with members, the evaluation explores the effectiveness of training and tools in instilling plain language practices in their work as adjudicators.

3 — Methodology

The evaluation draws on 3 lines of qualitative evidence drawn from diverse sources to assess how readable SST decisions are. The methods used to collect that evidence are described below.

3.1 — Interviews of SST members

In early 2022, the Accountability Unit of the Secretariat to the SST individually interviewed 13 randomly selected members from across the General Division Employment Insurance (GD-EI), General Division Income Security (GD-IS), and the Appeal Division (AD). The purpose of these semi-structured interviews was to identify how much plain language training and supports have influenced members’ outlook and choices in their approach to writing decisions, and how more readable those decisions have become. Appendix A: Interview guide of members provides the complete interview guide.

3.2 — Client survey

From February 1, 2022 to May 1, 2022, the SST emailed an online survey to unrepresented parties after they received their decision. The aim of the survey was to measure how these clients reacted to their written decisions in terms of clarity, understandability, and complexity. Their responses were then contextualized with additional information about the outcome of their appeal, and their education, official language, and other personal characteristics. Appendix B: Survey to clients lists the complete survey questionnaire and results.

3.3 — Analysis of decisions

In addition to user feedback, legal plain language specialists carried out a text-based analysis of a sample of 145 decisions by 40 different members. The specialists assessed these decisions for content, structure and style. That assessment produced detailed qualitative information that highlights the communication strengths of SST decisions as a whole and where follow-up attention may be needed. Their independent assessment relied on a rating methodology, which the SST designed specifically for this evaluation. Appendix C sets out the full methodology.

3.4 — Limitations

The evaluation sent an online survey by email to 1,140 parties who did not have a paid representative. The response rate was 14%, which is considered standard for a survey of this type. The margin of error is plus or minus 7% when the survey is run 19 times out of 20. That margin widens when reporting results at sub-group levels, such as division or official language group.

Unrepresented parties who consent to email communication with the SST comprise about 78% of the SST’s caseload. That represents the vast majority of the SST’s parties. However, those not surveyed because they lack email access may represent relevant socio-economic population groups, such as senior citizens, persons with low literacy, and low-income households.

The evaluation interviewed 13 randomly selected members from the GD and AD. Members’ aggregated feedback began to remain unchanged after about 10 interviews. As such, there were diminishing returns with each additional member interviewed. Given capacity constraints, the evaluation ended interviews after the 13th member. The sample of members isn’t intended to be representative of members as a whole.

4 — What members said

4.1 — Background and prior experience with plain language

Nearly all 13 members interviewed for this evaluation have been with the SST for at least 5 years. Before joining, the large majority were law practitioners working in the private sector, other tribunals, or the public service.

All of the 13 members write decisions in English. A few also write decisions in French. Almost all had some plain language experience, even if they didn’t define it as such at the time. The majority had prior experience writing or communicating legal matters to laypersons, such as clients or non-lawyer colleagues.

4.2 — Usefulness of training

All the members who were interviewed mentioned attending various SST-organized seminars, presentations, and workshops that were delivered since 2017. Some cited specific experts or organizations such as the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice (CIAJ), Association des juristes d'expression française de l'Ontario, Clear Language and Design (CLAD), and 2 former supremecourt justices.

All members valued the training received, including doing exercises and receiving practical advice.

“I really like when we have national training sessions. We spend several days learning techniques and resources that are quick and easy, like Hemingway editor.”

“At that training session we learned about various tools, like Antidote, and that’s where I focus my plain language efforts. That session helped me appreciate what proofreading tools could do for me.”

Many members highlighted CIAJ training as one of the best training sessions they had on plain language.

“The training we had from [the CIAJ] was the most useful for figuring out what you are trying to say, and then the best way to say it for the audience you're writing for. It had a better overview of why we were doing this, maybe because it was issue-based.”

“For sure the CIAJ training. It really dealt with structure, point-first writing, and all of that incorporated in templates that we use to remind ourselves. It was individualized; we would give sample decisions and get feedback on things we had written. After the training, we did a draft decision and were able to have it reviewed by one of the CIAJ facilitators and get comments before it was released. I found that one-on-one approach very useful.”

Some members liked that experts with a legal background shared practical tips and provided individualized feedback. One member, on the other hand, appreciated the opportunity to learn from someone outside the legal environment.

“I thought CIAJ were the best trainers because they have the legal background. The consultant who did the letters had a hard time giving advice.”

“The training I found extremely effective was the one with Clear Language and Design. I thought it was terrific and the facilitator was excellent. The fact that she was outside the legal world meant you could not rely on her background knowledge. The training and exercises were really good, and she did coaching afterwards where she would look at our decisions and send them back marked up. That was really useful too because it was a decision that I’ve actually written and sent out to the public.”

Members were exposed to different training opportunities, depending on when they were appointed to the SST. One member observed that more recent member cohorts are benefiting from more extensive training than earlier cohorts.

“I have been reviewing decisions of one of the new members from last year. Apparently, the people who started in the last year are much more trainable than those of us who are left over from 2021 or before. I think the training they have had has been very good. They got 8 or 10 weeks, we got 1 week. We kind of learned on the job.”

For one member, one of the trainings had recommendations that were too drastic considering how they used to write decisions.

“The plain language training from CLAD was too simplistic and it was too dramatic a change. It was focused on, for example, using certain words, instead of getting people’s buy in. Now we are to be writing for Grade 6 level. We are used to writing to impress people who seem to be impressed by long sentences and big words. I appreciate the resources they gave us, but I found the training itself was too drastic in the way it was delivered.”

Members’ opinions on the amount of training weren’t universally shared. One member felt they had more than enough plain language training while another found training was becoming a little repetitive.

“I think I can write well enough to be understood. I have been doing this for more than 4 years. That is enough. Do not make me do anymore plain language writing training.”

“I can't say that I have attended any training that has not been helpful. Some of it might have been a little bit repetitive, but even then, they are good reminders. I have never walked away from a training session thinking it was a waste of time or I did not learn something new.”

4.3 — Usefulness of tools

4.3.1 — Style guide

In 2021 the Secretariat to the SST released the Style guide: Social Security Tribunal of Canada decisions. This tool supports members to write in a more accessible and consistent manner by addressing linguistic and formatting issues.

The extent that individual members have adopted the style guide varies widely. Some members confirmed they reviewed and use the style guide. Most don’t use it frequently or just use it as a refresher. A few only reviewed the previous version. A few members said that they don’t have time or forget to check the guide when they are busy. One member doesn’t feel the need to go to the style guide because they already internalized its lessons. Another member doesn’t find it easy to retrieve information from the guide.

“It is a very useful document but it is one that goes a bit by the wayside. I tend to look at it when it first comes out, but not a whole lot afterwards. If I have a specific question, I might go back and look at it. But a lot of it is incorporated in the template.”

“The style guide only works if you commit it to memory. I do not find it is easy to look up and you have to know the mistake you are making to look it up. I do not use it much.”

One member appreciated that the French version of the style guide is not simply a translation of the English version.

“One of the things that I quite like about the style guide is that the French version is not simply a translation. They purposely created it separately, recognizing that writing in plain language in French is a bit different. I think that is a useful tool.”

One member shared that they don’t agree with some of the style guide’s recommendations.

“I’m not a huge fan of the style guide because I don’t agree with everything in it. When I am trying to write in plain language, I see how it sounds aloud. I try to write with active language and in present tense. I try to start every paragraph with the conclusion. The style guide has odd suggestions for punctuation, comments, and contractions. I will use contractions if I have to but I am not a huge fan.”

4.3.2 — Decision templates

The large majority of members use decision templates and find them a useful resource.

“I find they help me keep my thoughts gathered and in order. Sometimes in difficult decisions, it takes a while to settle down into an order of thought processes. It really helps me organize my analysis.”

“The templates are good when I’m short on time. I rely on them a lot for the statement of the law.”

“The templates I’ve seen recently are very well written. I like the language used in them.”

Most members described adapting templates to better suit their needs or because templates don’t match their personal writing style. For some, the description of legal concepts sometimes lacks precision. Other members created their own templates for more uncommon files. One member mentioned that they adjust the template based on the claimants, such as to include something that is important to them.

“They updated the templates but it doesn’t address every situation so one has to create one’s own template.”

“The template is useful to a point but there are some things that I personally don’t agree with so I correct them manually every time when I write my decisions.”

“My issue with the templates is that it’s very clearly not my voice. Sometimes, I find it too simplistic, too friendly, or too casual. As a member of a Tribunal and making a decision that could be published, I need to formalize the language a little bit more.”

For one member, templates are particularly useful when they are writing in their second language.

“I rely on the French templates a lot more. I adjust it less because French is my second language and I tend to defer a bit more to whoever worked on those.”

A few members were involved in creating templates. One member shared that they found the process valuable to understand the perspective of others.

“I was one of the members who worked on developing the template for X, so it was helpful even doing that exercise to hear other people's thoughts on ways to write things. Something in my mind might be okay, but then to hear someone else explain why it might be problematic, I found that whole process really valuable.”

For one member, there needs to be more consistency in the templates across divisions, such as in the use of the terms “claimant” versus “appellant”.

A few members would like to have more templates, especially for less common situations.

4.3.3 — Peer review

Some members participated in an informal peer review initiative in which members were matched to review each other’s decisions. They considered it a valuable experience because it helped them incorporate plain language strategies and catch issues.

“Once you start looking for those things they become easier to find. I think it changes the way you write. The plan is not to fix every decision now or rewrite it in the way we wish it had been done, but to highlight places where the writers might want to think about changing the language, and then hopefully that will snowball.”

Some members brought up challenges with peer review.

- A few commented that it is a very time-consuming process.

“If I do not have the time to get the decision to a colleague, wait for them to look at it, and review their comments because I am coming right up to the deadline, I do not use the process. I just cannot afford to be late with decisions.”

- Another member thinks peer review would be less effective because members aren’t laypersons.

- A few members expressed hesitancy about receiving individualized feedback, but believed that it could be a helpful process.

“I think peer review would be good for me, but I’d be nervous doing it. I am personally a little uncomfortable with getting people to review my files, but I think it would not hurt. If we were instructed to do it, I’d do it.”

4.3.4 — Proofreading software

Most members confirmed they use proofreading software such as Antidote, Hemingway, or the Word review function. They check paragraphs or entire decisions to assess readability or grade level and to catch things that they would otherwise miss, such as passive voice and long sentences.

“I heavily used Hemingway. It grades your reading level and highlights things, like if the sentence is too long. If you are using words that are too complex, it will suggest a replacement. I find that really, really useful.”

“If it is something I do not write about often, I will go to the Hemingway app and see what it catches. Inevitably it is something complex like reconsideration decisions or delays, or where I’m quoting the law directly.”

Two members revealed they don’t yet have Antidote installed on their computer. For some others who do, they stated a preference for Antidote over Hemingway because it has better capabilities.

“It [Antidote] catches a lot of things that when you’re writing quickly you may not catch yourself. (…) I always check the readability index. The grade level always goes down after using it”

“I kind of stopped [using Hemingway]. It’s not as sophisticated as Antidote. It really just measured the length of sentences and words.”

For one member, Antidote is useful when writing decisions in their second official language.

“I tend to play around with my language a lot more in French. I will go into Antidote and if it flags extra-long sentences, I will try to simplify it. I tend not do that so much in English.”

Yet other members use proofreading tools less often now because they find that they have already internalized the usual recommendations.

“When I first did the training, I used Hemingway. It did get me to do things that I just started to incorporate more often, like shortening my sentences. In the early days, it helped me to get where I needed to be.”

For one member, the tools weren’t as helpful because they didn’t agree with what they recommended.

“I haven’t used [proofreading tools] recently at all. I just got frustrated more than anything. I did not feel like I was getting the value for time it took. Some of the suggestions were things that I just could not see what the problem was and there was not a good enough explanation of the issues.”

4.4 — Professional development needs and potential new interventions

4.4.1 — Training

The majority of members would find additional plain language training helpful and be inclined to take advantage of any future training.

“The formal training that we had was very useful because it carved out time for people to focus on that. It directed us to tools that we could use while we were writing. I found that was a really good start. The message was “here's the thing that you need to start thinking about”, and that to me is the main thing: start thinking that this matters and it matters enough that we will give you the time to do it.”

A few of those members specifically requested further CIAJ training. Other members recommended going outside the usual providers, such as a training session with Justice Pazaratz2 of the Ontario Superior Court or certain clarity advocates who have appeared on social media. A few members didn’t agree that further plain language training would benefit them. A couple of members said they were content with the amount of training received to work effectively in plain language, and one discussed a need for an emphasis on legal training instead.

“I think balancing out what is going to save me the most time, what's the most efficient thing to do, that would be legal training, not plain language. […] I think the biggest help would be training which we give ourselves through [the] professional development committee.”

4.4.2 — Individualized feedback

The majority of members felt that individualized feedback would be valuable in refining their plain language writing skills.

“One-on-one advice for me is always the most useful. Where someone is looking at something I produced.”

Members appear open to feedback from a wide array of sources. A few members wished for more:

- Peer review

- Individual coaching as part of formal training

“Individual coaching [from Sally Macbeth] was one of the most practical and useful tools we were given. If we were offered that again, I would definitely take advantage of it. Just to have that feedback was useful.”

- Increased feedback from Linguistic Services and Legal Services

- Feedback from laypeople

“It’d be helpful to find people here at the Tribunal who know nothing about EI and set up an internal ad hoc thing to have them available to read the decision.”

4.4.3 — Other suggestions

More plain language tools and guides would be helpful for a few members. In particular, the usefulness of templates and a desire for more of them was raised multiple times.

“In order to have good templates, we need templates on every kind of decision. I’ve made my own templates, but it would be nice to have a list right in the database. I get the impression that the Tribunal wants there to be a common look in our decisions, so templates would help.”

A few members mentioned the need for the SST to adjust its expectations of members to reflect the labour-intensiveness of plain language writing, and to provide clarity about its priorities. The competing demands of producing timely decisions, attending to files, and attending meetings often take precedence over the time needed to write in plain language. Plain language writing becomes something that members do if they have time, rather having the necessary time carved out for them.

“I’m not sure that the message has gotten across yet. Our performance standards have not changed in years. I think other people feel stressed about producing on time, rather than taking extra time to produce in plain language.”

“We all developed our own precedents and we copy and paste from ourselves. I don’t know if there is a way to do that but maybe dedicating some time for members to work on their own precedents. I don’t know, maybe giving it one less case this month or instead of having our AD meeting this week we’re all going to work on our personal decision templates.”

Whether as part of formal training, or internally within the SST, reminders of plain language goals and best practices would be useful, in the view of a couple members.

“This was a big focus for a long time. It has been less of a focus recently and maybe we need a way of reminding members. Refreshers on what is there I think would be helpful. I think this is what the pilot project at the AD did. Just a kind of reminder to keep thinking about this.”

Similarly, reminders of the resources available may be useful in the view of a couple members.

“I don't know what I don't know. I don't know what other kinds of resources are out there that might be valuable that I'm just not aware of.”

Despite its widespread adoption, plain language hasn’t been universally accepted among members. One member shared that it is a challenge for some people to buy into the idea that improving decision readability is a worthy goal.

“I would say most people at least pay lip service to it. A couple of people don’t; one member called it baby talk. They are not around anymore, but they actively resisted it. Most people buy into it but not to the extent that they will take more time if they are feeling time-pressured.”

Another member wondered whether claimants actually read decisions and if it would be worthwhile continuing to invest in plain language.

“I think it’s important to know whether the appellants actually read the decisions before investing resources in plain language.”

Further below in section 5.3 Most decisions are read in full, the study found that 87% of unrepresented parties surveyed claimed they read the entirety of their decision. Regardless of the actual readership, in the next section members share how plain language has intrinsically benefitted both their decisions and how they communicate with SST clients.

4.5 — Perceived access to justice improvements credited to plain language

A few members shared that plain language skills are important because it helps them better communicate their decision and reasoning to clients. For these members, being accessible and understood is a critical aspect of their work and clients’ access to justice.

“Our job is to deliver justice. If people don’t understand my reasons, even if the result is just, I feel like I did not do my job. I think it’s a critical component of the work.”

“The most important thing about my work is that I explain to people why I decide what I decide. If I cannot write in a clear way, I cannot get my reasons across. To accomplish what I’m appointed to do, I need to use clear language.”

“I’ve written decisions where the person calls and ask if they win or lose. I think I failed pretty badly in writing when that happens.”

As one member explained, if clients are able to understand decisions they will be more inclined to accept them.

“From our perspective, in terms of decision-writing, we feel that if they actually understand what we’re saying they’re more likely to accept our decisions.”

One member observed that plain language is important because clients may not feel comfortable sharing when they didn’t understand something.

“They’re already scared coming here, already intimidated. The last thing they want to admit is that when I tell them this [legal] definition they have no clue what that means. They want to seem confident. They want to seem like they know what we’re talking about.”

All members perceived their decisions as being improved or better compared to their older decisions. Some noted that plain language strategies made their decisions more concise, easier to read and understand. One member shared that they enjoy reading decisions more when written in plain language.

“The decisions are definitely better. If I read my decisions from years ago, I find them very wordy. I think plain language makes you focus on what’s important.”

“They are getting better. I still feel like I have work to do, but they are better than they were.”

A few members are unsure whether their decisions are now easier to read because they don’t hear often from clients.

“I would hope [that my decisions are easier to read]. I can't say for sure because I don't get that feedback from the appellants about whether they understood my decisions.”

“If you compare older decisions, you can absolutely see the difference. (…) Hopefully, the advice we get is good and people would agree that this is more understandable. [It] certainly makes sense to me that it is more accessible.”

A few members monitor the notional grade level of their decision with software to mark progress made.

“I think my decisions are quite a bit easier to read. I usually check my decision in Word or Hemingway. It is rare for me to write above a grade 9 level, unless it is something very complex. When I first started, I would often get above a grade 12 [level].”

Some members observed a possible unintended consequence of plain language efforts, that is, that decisions of the SST tend to become standardized in their writing style and how they read. A few other members are uncertain about how that would be perceived or whether that should be a goal.

“Sometimes, I can’t even tell if I wrote something. With plain language writing, it’s not uniform, but it’s more consistent on how people write.”

“One of the things that concerns me is if too many of the decisions from multiple decision- makers are too much the same. I wonder how that would be perceived externally.”

Some members noted that adopting plain language has produced benefits that extend beyond decision-writing to other ways they engage and communicate with clients. They explained that plain language has helped them to think more critically about clients’ ability to read and understand decisions.

“Before having taken the training, I was not aware of how the average person might be able to understand my decisions.”

“As lawyers and members we don’t necessarily think about what is more accessible. It is really important that we be reminded that these are the ways that our particular clientele will find more accessible.”

Further, in the hearing room, a few members related that they apply plain language skills when speaking with clients, and this creates clearer understanding and testimony. One member shared that, even outside work, they now think more carefully about how they communicate.

“I feel like I’m communicating better with appellants. From an access to justice point of view, I feel better about how we’re communicating when I’m not throwing them more than I need to.”

“To me it is horrific that someone can lose not because the law is against them, but because they didn’t tell me something because they didn’t know it was important. If I get super technical, I’m going to get worse information from them.”

“The skills we’ve developed on plain language should extend to all forms of communications. They should really stress that it is not just plain language writing, but plain language communication skills.”

A few members try to write using the same language or approach they used at the hearing to make it easier for claimants to understand the decision.

“I find the hearing is a useful way of coming up with a way to explain things in a plain language style because you get instant feedback. I try to remember how I have said things at the hearing and use that language in my decision.”

“When you explain the legal test in a hearing, you want to use that same explanation in the decision, because that is what is in their head. When they get the decision and all of a sudden there is a whole lot of complicated things, they get confused.”

“I try to remain true to the language the appellant uses during the hearing. If an appellant is using certain words over and over again during a hearing, that is a cue to me that those words are important to that person. And even though those words may not be plain language words, I will use them in my decision because it's showing the appellant that I was listening.”

Some members adapt the language to match the circumstances of the claimant, such as their education or first language.

“I try to customize my writing to the particular case I’m involved with. If I’m dealing with immigrants whose first language is not English or French, I’ll try to be super plain and simple.”

“I do have some cases where I don’t put a heavy effort on writing at a lower grade level because the participants are highly educated. On the other side, if I have an appellant that just isn’t even following along in the hearing, I’ll spend extra time explaining what the legal test is until they understand that.”

Recommendation # 1

Different members naturally find varying levels of usefulness in the different supports available to them, whether the style guide, templates, training sessions, software, or others. However, some members noted that they don’t have access to or aren’t aware of the full range of resources available. One cited example was Antidote. The member resources site on SharePoint, which serves as a repository of member supports, should be kept up to date and all members should know how to access this site to further their plain language skills. These tools, supports and the SharePoint site should be included in new member learning programs.

5 — What clients said

During a four-month period in early 2022, the Secretariat to the SST emailed an online survey to parties who did not have a paid legal representative. The survey questioned them on their views of the readability of their decision and analyzed their responses set against information about their appeal and socio-demographics. Appendix B: Survey to clients describes the survey’s methodology.

5.1 — Clarity of the outcome

Figure 1 — When you first read the decision, was it clear whether you won or lost?

Text Version

Yes: 62%

No: 19%

Somewhat: 19%

Number of respondents = 155

Upon receipt of their decision, every party should be able to quickly find the outcome. The survey revealed that 62% of respondents knew right away if they had won or lost their appeal. That figure does not vary significantly by division or stream (67% in the AD, 63% and 58% in the GD-EI and GD-IS, respectively).

Nor does one’s educational background appear to be an advantage: 67% with a university education knew the outcome right away; 61% of clients without university education said the same – within the margin of error.

However, a notable 20-point spread was found between official language groups: 79% of French readers knew their outcome quickly versus 59% of English readers. Among English-speaking respondents, the subgroup with the most difficulty were high school-educated clients before the GD-EI – only 47% recognized their decision quickly.

Overall, the group reporting the most difficulty were claimants who lost their appeal: 38% of these respondents reported not knowing their decision right away versus 6% of respondents whose appeal succeeded – a 32-point spread. Indeed, the strongest correlation throughout the survey’s questions was the outcome of one’s appeal. On every question asked, unsuccessful claimants3 reported the most difficulty with their decision.

A few respondents shared that the decision outcome should be stated more clearly at the beginning of the decision.

“Put the decision at the beginning versus the end.”

“Just state ‘denied’ or ‘approved’ at the beginning of the page, then all the other stuff explaining why.”

“[It] would be clearer to know and understand that the decision made is in your favor or not; that part I found was a bit difficult to understand; however, after reading it a few times, it became clearer and clearer and finally we understood and we're happy with the decision. Thank you!”

“Decision should be at the beginning and easier to read. Then the steps to appeal this decision should be spelled out. Then the for-and-against arguments from the arbitrator [member].”

The evaluation found that all sampled decisions but one announced the outcome upfront in paragraph 1 (and to a lesser extent, paragraph 2). Despite this prominent placement, many readers still report difficulty. For example, before reaching paragraph 1, a claimant must go through 3 to 6 preceding pages from the SST consisting of: an email cover message, a one-to-four-page cover letter, the decision’s cover page, and then the decision itself. The style of paragraph 1 varies among members, but it typically states whether the appeal is allowed or dismissed. Sometimes, it specifies whether the appeal is in favour of the appellant or respondent. Fewer still cite the parties by their name. As such, lay readers may find themselves having to flip black to the cover page to cross-reference legal terminology and decide if they fall under the winning party.

5.2 — Complicated wording

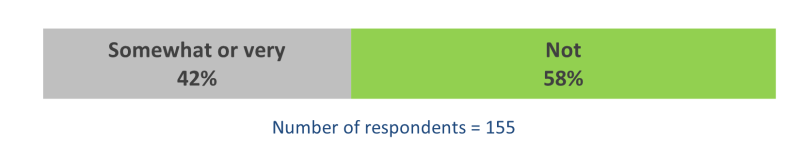

Survey respondents reported that 58% of them didn’t find the wording of their decision to be complicated, and 42% found it very or somewhat complicated. (See Figure 2 below)

Figure 2 — How complicated was the wording?

Text Version

Somewhat or very: 42%

Not: 58%

Number of respondents = 155

Broken down, English-speaking respondents with high-school education struggled the most; 59% said the wording was very or somewhat complicated. The majority of them reported they had to rely on someone else to help them understand the decision.

Similarly, respondents whose appeal was successful or unsuccessful reported extremes between not complicated versus very or somewhat complicated. (See Figure 3 below)

Figure 3 — How complicated was the wording by outcome

Text Version

Successful claimants

26%: wording complicated

74%: wording not complicated

Unsuccessful claimants

65%: wording complicated

35%: wording not complicated

Comments left by respondents offer some insight:

“A definition section in layman’s terms for all involved parties. It was confusing trying to understand who ‘I’ was referring to in the document, along with trying to follow the subjects ‘commission’, ‘tribunal’, ‘appellant’.”

“At best I struggle with legalese so I had to reread a few times to understand.”

“It was hard to figure out the wording since some paragraphs contradicted each other.”

[Translation] “I was stressed, and I had to read it twice to understand that I won.”

“Suggest for easier legibility to highlight the desired items to prove your case in bullet points.”

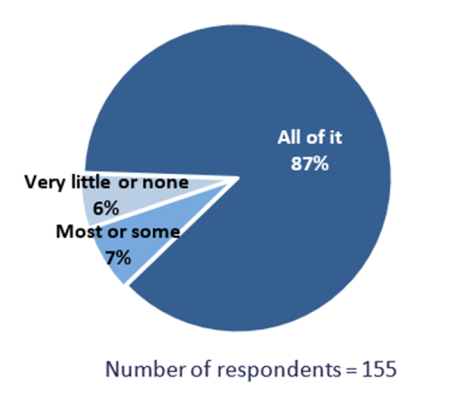

5.3 — Most decisions are read in full

Figure 4 — Most decisions are read in full

Text Version

All of it: 87%

Most or some: 7%

Very little or none: 6%

Number of respondents = 155

The survey found that 87% respondents read all of their decision. The data suggest 3 likely factors.

First, those with university education, who made up 38% of all respondents, were the likeliest to have read all of the decision.

Next, French readers were also somewhat more likely to have read all of their decision than English readers.

The biggest factor was outcome – 93% of successful claimants read all of their decision compared to 79% of unsuccessful claimants. That number declines to its low of 74% who have neither university education nor legal representation. This figure highlights the disincentivizing effect of a negative decision among some socio-economic groups to reading and understanding their decision in full.

5.4 — Help to understand the decision

Figure 5 — Did someone help you to understand the decision?

Text Version

Yes: 31%

No: 68%

The majority, 68%, said they didn’t need someone’s help to understand the decision. Of the 31%, or 49 parties, who did need help, 19 had the help of a personal representative and 30 found help from someone else.

Asked to suggest what could make decisions easier to read, respondents chose the following options in Table 1:

Table 1: What else could make decisions easier to read?

x |

# of responses |

as a % of all respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Explain what will happen next |

25 |

16% |

| Spell out result |

23 |

14% |

| Use less technical terms |

13 |

8% |

| Make the decision shorter |

12 |

7% |

|

Number of respondents = 65 |

||

The desire for more information on next steps from 16% of respondents was a common theme in the survey. The Secretariat’s cover letter to the decision does outline next steps including the claimant’s appeal rights and follow-up actions by Service Canada. But after having read and considered their decision, many claimants evidently weren’t aware of or didn’t make the connection to refer back to the cover letter.

“It [the decision] states: ‘I am giving the Claimant permission to appeal and allowing the appeal. I am returning her Application to Rescind and Amend to the General Division to be decided again, by a different member’. What I'm not necessarily clear on is next steps. I think I wait to be contacted by the GD, but this wording makes me wonder if the next steps is for me to appeal again??? Like, do I need to fill out paperwork? I don't think so… Anyways, having a next steps here would be helpful, just to clear up any confusion. Thank you.”

[Translation] “The decision read clearly. However, I would like more information about the procedures and steps to take once the appeal is successful.”

[Translation] “I called the number given for information today, and my bubble burst when she told me that the commission had 20 days to protest this decision?”

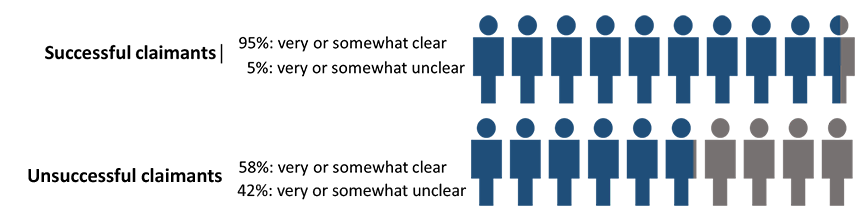

5.5 — Overall clarity and understandability

Overall, 81% of respondents stated they found their decision very or somewhat clear and understandable. The underlying correlations with specific subgroups tend to mirror the findings in earlier survey questions.

Among university-educated respondents, 88% reported their decision was very or somewhat clear and understandable while 81% and 72% said so among college- and high school-educated respondents, respectively. GD-EI English-speaking respondents with high school education were the least likely to have agreed at 65%.

Figure 6 — Decisions overall are clear and understandable by appeal outcome

Text Version

Successful claimants

95%: very or somewhat clear

5%: very or somewhat unclear

Unsuccessful claimants

58%: very or somewhat clear

42%: very or somewhat unclear

The outcome of one’s appeal again correlates with opposing views – 95% of successful claimants agreed their decision was very or somewhat clear and understandable while 58% of unsuccessful claimants said the same.

What the data doesn’t address whether an allowed or dismissed decision drives a behavioural or attitudinal position on a decision’s readability. Unsuccessful claimants were about 40% less likely to have participated in the survey and when they did, consistently rated their decision lowest for outcome clarity, complexity, length, overall clarity and understandability. This may be a function of respondent bias. It may also be a function of the demands that an unfavourable decision imposes on losing parties. They face the discouraging burden of having to go through the decision to make sense of why they lost and what it means going forward.

The open-ended comments left by unsuccessful claimants show mixed engagement with their decisions. Some comments are angry and dismissive. Most, however, are restrained and even constructive:

“Suggest for easier legibility to highlight the desired items to prove your case in bullet point.”

“It was hard to figure out the wording since some paragraphs contradicted each other.”

“Although it was a very lengthy case, this decision did not really make sense. Many questionable things occurred throughout the process and the decision spent a lot of time doubting what I had said rather than remaining impartial which was required of the tribunal member. I do have many questions that I understand will not be answered. The level of detail was appreciated but as it didn’t really make sense, it was unnecessary.”

“I was not happy with the decision as it was cut and dried, with no understanding that the hours of requirement changed ONE week before my lay off at my job. If I would have realized that, I would have gone to my boss and ask to work the extra hours to meet the EI requirement. At 85 years old, it takes a lot of dedication and hard work to keep up with the cost of living.”

“Decision should be at the beginning and easier to read. Then the steps to appeal this decision should be spelled out. Then the for-and-against arguments from the arbitrator [member].”

These comments and others suggest that many unsuccessful claimants made at least a fair attempt under the circumstances to appreciate why they lost. They may have been disadvantaged by personal barriers, such as low literacy or lack of a legal representative, to fully access their decision. Those barriers could be addressed through future Tribunal actions, recommended as follows:

Recommendation # 2

Make clearer the appeal outcome right from the outset of the decision. Two possible approaches could be:

- State the outcome earlier, such as in the cover letter. The cover letter of decisions that refuse leave or summarily dismiss already state the decision, and this practice could extend to merit decisions.

- Consider alternatives to the terms “claimant”, “appellant”, and “respondent” by using, for example, the claimant’s initials to make it easier for people to find themselves in the decision.

Recommendation # 3

Claimants both successful and unsuccessful expressed a desire for clarity regarding what happens after the decision. Although the decision cover letter sets out such information, consider ways to reinforce the messages found there.

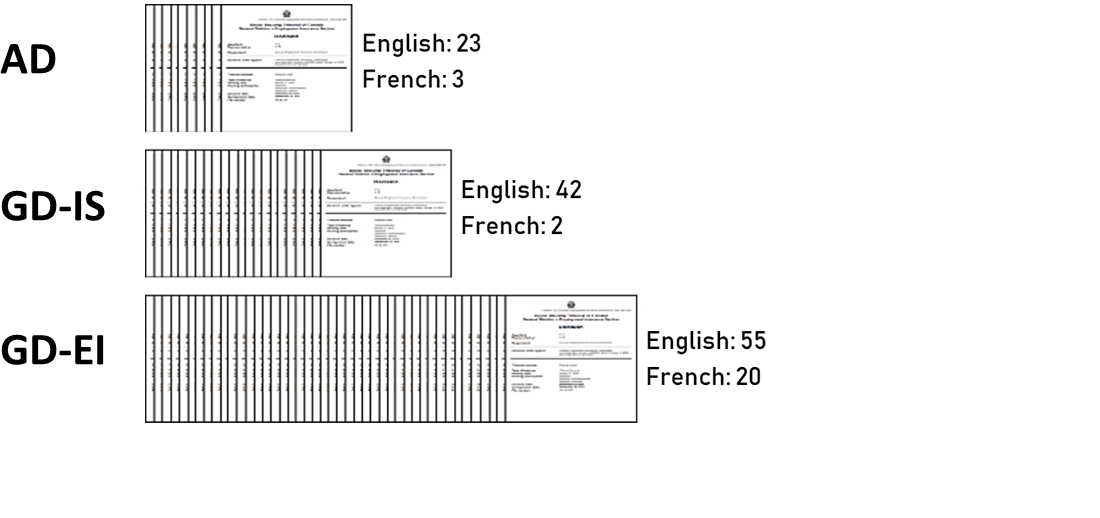

6 — What the experts found

6.1 — Background

The evaluation contracted a third-party firm to impartially assess a sample of decisions for their readability. The firm assigned 2 of its specialists, one for each official language, to critique each decision against 18 elements of decision-writing covering structure, style and substance. The Secretariat’s evaluators then aggregated and analyzed results to reveal broad areas of decision-writing strength and areas needing attention4.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 below break down the number of decisions and members sampled across the SST’s appeal streams. The Secretariat’s evaluators provided the contractor with 145 randomly selected, redacted decisions from 40 members who have at least 1 year of experience at the SST. All 145 claimants were unrepresented. All decisions were made at least 6 months after the members received the most recent plain language interventions in 2021 – the release of the SST style guide and decision templates. These tools provide members with guidance on linguistic, formatting, and structural issues, and build on the suite of tools and training provided to members since 2017.

Figure 7 — Distribution of members sampled

Text Version

AD: 7

GD-IS: 14

GD-EI: 20

Note: Total members is 40 but the chart counts a member twice if hearing appeals in both the GD-EI and GD-IS

Figure 8 — Distribution of decisions sampled

Text Version

AD

English: 23

French: 3

GD-IS

English: 42

French: 2

GD-EI

English: 55

French: 20

6.2 — Decision contents

6.2.1 — Why we measured this

Every SST decision is expected to include only essential contents and background information that allow the reader to follow the member’s thought process.

6.2.2 — What the results say

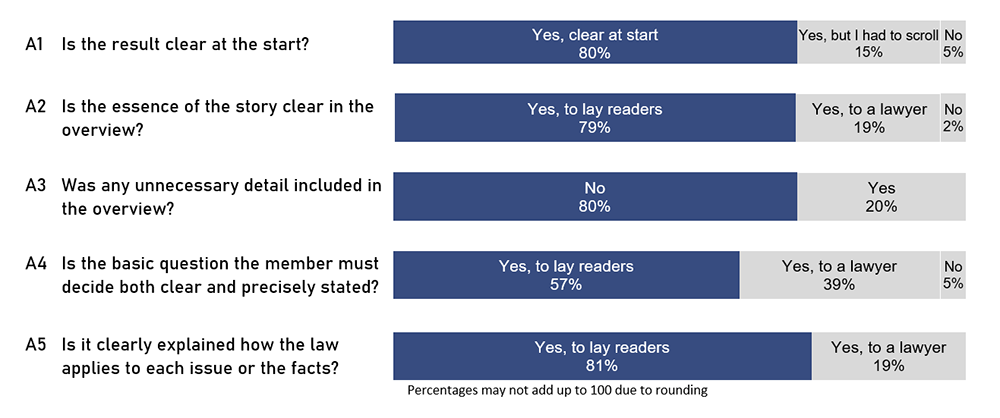

Text Version

This picture shows the responses in percentages to five question labelled A1 to A5.

In response to A1, Is the result clear at the start: 80% chose yes clear at the start, 15% chose yes but I had to scroll, and 5% chose no.

In response to A2, Is the essence of the story clear in the overview: 79% chose yes to lay readers, 19% chose yes to a lawyer and 2% chose no.

In response to A3, Was any unnecessary detail included in the overview: 80% chose no, and 20% chose yes.

In response to A4, Is the basic question the member must decide both clear and precisely stated: 57% chose yes to lay readers, 39% yes to a lawyer, and 5% chose no.

In response to A5, Is it clearly explained how the law applies to each issue or the facts: 81% yes to lay readers, and 19% chose yes to a lawyer.

6.2.3 — What the key findings are

Decisions showed widespread strength with approximately 80% presenting at a lay level:

- a clear statement of the result at the start

- a lean introduction from which readers could understand the essence of the appeal

- clear explanations of how the law applies to the issues or the facts

The finding that results were clear at the start would appear to contradict the 38% of surveyed clients who found the result difficult to find or grasp. Experts did observe why lay readers could struggle here. The result is often written in ways laced with jargon or unclear language. This jargon includes: “leave”, “without just cause”, “I don’t have jurisdiction”, “her election was irrevocable”, and “concession.” It may also include double negatives — “not being disqualified” and [translation] “This signifies that the claimant is not inadmissible.”

In other decisions, the result statement is clearly articulated, but it isn’t contained within a dedicated “Decisions” section, as recommended in the style guide, nor complemented by an explanation of what it means or the consequences for the claimant. Such a follow-up would underscore the result and render it more immediate.

The study did find effective examples that used the Decision section to explain both the result and its consequences. This technique could be considered a shareable practice in all decisions. One example found, based on the GD-EI decision templates, is:

[Translation]

Decision

[1] The appeal is dismissed.

[2] The Claimant hasn’t shown that she had good cause for the delay in applying for benefits. In other words, the Claimant hasn’t given an explanation that the law accepts. This means that the Claimant’s application can’t be treated as though it was made earlier.

Question A4 was the lowest scoring question. It assessed if the basic question the member must decide was both clear and precisely stated. Some decisions articulated the basic question within the overview section, but most did so within a discrete issues section, as is recommended in the style guide. Regardless of location, the study found 57% of decisions expressed the basic question in terms that a lay reader could understand, and 39% did so at the level of a lawyer.

Between divisions, the GD as a whole averaged 63% while the AD scored 27%, a difference of 36 percentage points. Within the AD, merit decisions averaged 23% versus 31% for non-merit decisions. Between the official languages, French decisions expressed the basic question clearly 72% of the time versus 53% for English decisions.

What often made the difference when scoring A4 was that members made efforts to paraphrase or explain the law and jargon when stating the issues under appeal. Common jargon that was left unexplained included “just cause”, “reviewable error” and “arguable case.”

Question A4’s 57% score contrasts with question A5 which similarly assesses whether the law is explained as it applies to each issue or the facts. Here, 81% of decisions made effective efforts to explain the law, indicating improvement is feasible by extending the same clarity and attention to the basic question under appeal.

6.3 — Structure

6.3.1 — Why we measured this

Readers best understand and retain complex information if it is structured in a smooth and logical manner. A well-structured decision also contains markers laid down by the member – such as headings, topic sentences, transitions – that allow the reader to follow the member’s chain of analysis.

6.3.2 — What the results say

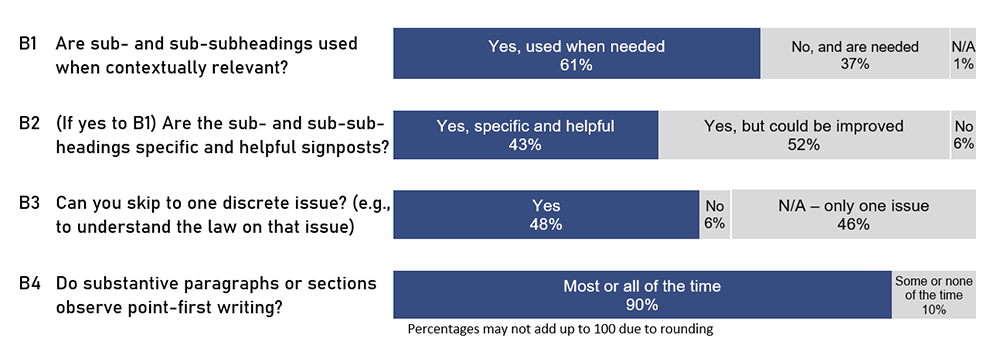

Text Version

This picture shows the responses in percentages to four questions labelled B1 to B4.

In response to B1, are sub- and subheadings used when contextually relevant: 61% chose yes used when needed, 37% chose no and are needed, and 1% chose not applicable.

In response to B2, (If yes to B1) are the sub and sub-sub-headings specific and helpful signposts: 43% chose yes specific and helpful, 52% chose yes but could be improved, and 6% chose no.

In response to B3, can you skip to one discrete issue? (e.g., to understand the law on the issue): 48% chose yes, 6% chose no, and 46% chose not applicable – only one issue.

In response to B4, do substantive paragraphs or sections observe point-first writing: 90% chose most or all of the time, and 10% chose some or none of the time.

6.3.3 — What the key findings are

The evaluation found that nearly 9 in 10 decisions apply point-first writing, the practice of stating the proposition before developing that proposition further. In the remaining decisions, members generally made a good effort to do so, but were scored lower for:

- sections that don’t start off point-first

- the major point isn’t logically supported by the underlying factual explanation

- confusing first points that outline arguments from both parties

The score of 90% would indicate that point-first writing, like any skill, improves with practice. That the vast majority of members consciously write point-first confirms that this method of explaining complex material has taken root.

That improvement could extend further when combined with other writing techniques, such as the use of headings and short sentences and paragraphs. However, the study found that only 6 in 10 decisions used headings and sub-headings when they were needed to guide readers through long or complex information. And among those decisions that used headings and sub-headings, less than half, or 43%, were found to be clear and helpful. The remaining decisions featured headings that:

- included jargon

- lacked necessary information to be helpful

- didn’t correspond to their content

- were part of a confusing hierarchy of headings and sub-level headings

Of the 37% of decisions that didn’t use headings, the common finding was the use of only one heading for long stretches of text spanning anywhere from 2 to 12 pages. In these decisions, sub-headings were needed to break down contents and inject relief.

Recommendation # 4

Members could be reminded of the need to help readers with headings and sub-headings that are clear, content-specific, and useful to guide the reader through long or complex material.

6.4 — Style

6.4.1 — Why we measured this

The SST trained members and provided supportive tools to encourage clear and consistent communication. Clients are more likely to trust that their appeal was fairly decided if the style of writing is simple and plain versus one that is opaque and legalistic. This section assesses different elements of writing style promoted in the SST Style Guide.

6.4.2 — What the results say

Text Version

This picture shows the responses in percentages to nine question labelled C1 to C9.

In response to C1, are footnotes used when needed (such as, in lieu of block quotations): 82% chose yes, 17% chose no, and 1% chose not applicable.

In response to C2, if legalese or jargon is used, are they explained or paraphrased in plain language: 63% chose yes, 33% chose no explanation or paraphrase, and 3% chose not applicable.

In response to C3, is there unnecessary use of nominalizations5: 78% chose no, only used when necessary, and 22% chose yes.

In response to C4, is there unnecessary use of acronyms and initialisms: 96% chose no, used only when necessary, and 4% chose yes.

In response to C5, are sentences short and expressing only one idea per sentence: 50% chose most or all of the time, and 50% chose some or none of the time.

In response to C6, are paragraphs short (no more than 6 lines): 74% chose most or all of the time, and 26% chose some or none of the time.

In response to C7, does the member use list format when listing more than 3 items: 46% chose most or all of the time, 8% chose some or none of the time, and 46% chose N/A-no list needed.

In response to C8, do sentences have clear actors: 93% chose most or all of the time, and 7% chose some or none of the time.

In response to C9, are there obvious writing errors? (for example, typos, grammar mistakes, format issues): 94% chose none or almost none, and 6% chose some or many.

6.4.3 — What the key findings are

Among the stylistic strengths found in the decisions sampled, the study noted:

- little unnecessary use of acronyms and initialisms, indicating the member’s awareness of reader sensibilities

- English sentences in the passive voice with clearly understood actors, indicating restraint when choosing to write in the passive voice

- minimal surface errors, indicating effective proofreading

- generally adequate use of footnotes, although some citations could appropriately have been placed in footnotes, paraphrased or integrated into the body of the decision

Among areas meriting attention, the study found ongoing use of jargon that wasn’t explained or paraphrased. This extends beyond the use of jargon in specific instances described above to the document as a whole. The examples of legal jargon are too many to list comprehensively, but include: “properly allocated the award”, “established the overpayment”, “varying the requirement”, and “natural justice.”

Medical jargon, an entirely different category of jargon, was also observed sometimes without adequate explanation. These terms included: “neuropathies”, “accommodated work”, “long-term disability carrier”, and “unable to function in a vocational setting.”

The analysis found that only 50% of decisions were comprised largely of short sentences expressing 1 idea per sentence. Plain language writing is known to generate more words but drawing out sentence length in combination with multiple ideas or concepts works against readability. Complicated sentences marked with dependent clauses and exceptions include the following:

“The Claimant cannot get all the weeks of benefits she is requesting as, when you combine regular and special benefits in a single benefit period, and maternity and parental are special benefits, you cannot be paid more than 50 weeks of benefits, and the Claimant has already been paid 50 weeks.”

[Translation] “The appellant disagrees, essentially he explains that had he known, he would have asked for his training to be authorized, he also says that had he known that he wasn’t entitled to benefits, he wouldn’t have prioritised his studies and he points to some of the employment steps he has taken.”

Recommendation # 5

Members could be reminded to continue to minimize the use of both legal and medical jargon and, when using jargon, to explain or paraphrase their meaning, as appropriate.

Recommendation # 6

Members could be encouraged to keep sentences short by breaking up ideas and making each one the subject of its own sentence.

Overall, decisions made against the claimant scored marginally lower than decisions made in favour of the claimant. This was the case in most of the elements of style, content and structure. This finding by third-party experts lends weight to findings made in the client survey when unsuccessful claimants reported higher levels of complexity in their decision.

Recommendation # 7

This evaluation reviewed several exemplary decisions in English and French. These decisions could be leveraged for teaching purposes in new member learning sessions. As research participants for this study, the members’ consent would be necessary before release.

7 — Conclusion and recommendations

The direction from the Supreme Court of Canada holds that decisions “must be justified, intelligible and transparent, not in the abstract, but to the individuals subject to it.”6 This evaluation explores whether the SST’s efforts are producing plain language decisions that meet the high court’s standard at a level accessible to lay readers. It enlisted both clients and experts to offer their feedback to that question, with members rendering context on the delivery side.

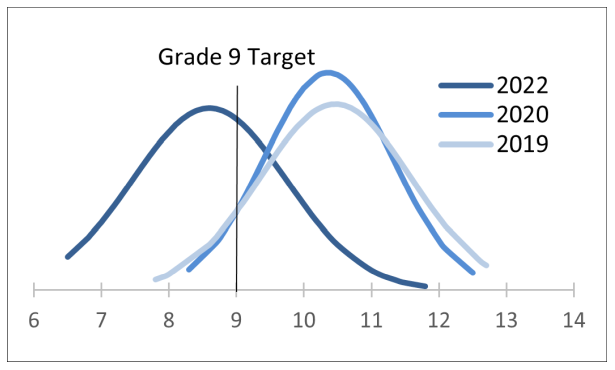

A straight, arithmetical crunching of the syllables, words and sentences computes an overall average reading grade of 8.6. (See Figure 9 below.) This betters the SST’s target of 9.0 and previous years’ averages of 10.4 and 10.6. Nearly all major sub-groups surpassed the target with AD and French decisions averaging the highest grade at 9.3.

Figure 9 — Flesch-Kincaid grade reading level has improved

Based on a sample of decisions on appeals without a paid representative

Text Version

Average reading grade

2022: 8.6

2020: 10.4

2019: 10.6

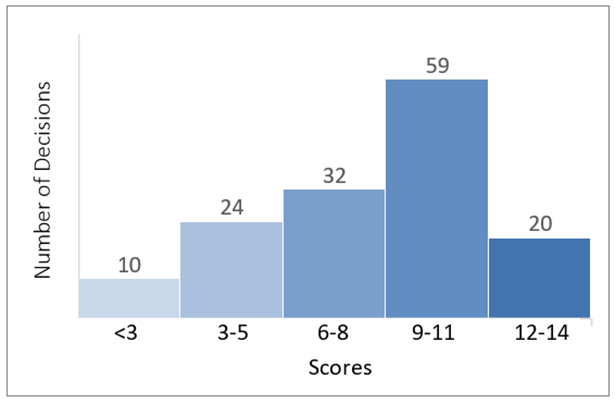

To complement the grade-reading formula, we measured qualitative determinants of readability that help the SST’s clients – content, style, and structure. These measures produced individual decision scores ranging from -1 to 14 out of a possible 14 points. Figure 10 below charts where the 145 decisions fell along that scale.

Figure 10 — Distribution of decision scores

Text Version

Score less than 3: 10 decisions

Score 3-5: 24 decisions

Score 6-8: 32 decisions

Score 9-11: 59 decisions

Score 12-14: 20 decisions

Over half the decisions (55%) scored between 9 and 14 points. What typically made this tier of decisions more readable were: a reasonably clear statement of the result; a succinct overview of the story; and a plain language explanation of the applicable law. Their analysis section was organized point-first with a deliberate effort to limit jargon and minimize acronyms, long sentences, passive voice, and nominalizations.

Do Flesch-Kincaid grades match up with qualitative scores? The study found a moderate correlation (𝑟 = -0.4) between the 2 rating schemes, meaning that overall, decisions that read at a low grade (that is, shorter words and sentences) also scored better on content, structure and style. This suggests that members don’t write to beat instant readability statistics on their word processor, but consciously draw on their training and tools to craft a readable document, just as they explained in interviews.

The plain language resources that members draw on are very much individualized. Each resource resonates differently for different members. But what most members seemed to agree on is they appreciate having the full menu of resources, time to consider them, and time to practice them in hearings and decisions.

What the client survey adds is the real personal factors that influence readability. The data show that lower education levels, one’s language fluency, low literacy, and the lack of access to a support person can act as barriers to engaging with one’s decision. However, the data equally show that claimants aren’t doomed by these disadvantages. For example, of the 95% of claimants whose appeal succeeded found their decision to be clear and understandable, less than one-third had university education. This suggests that readers make the effort, especially when presented with the pull of a successful outcome. The challenge is to overcome the push of a negative decision. Opportunities to improve decision engagement are restated in the recommendations below.

Recommendation # 1

Different members naturally find varying levels of usefulness in the different supports available to them, whether the style guide, templates, training sessions, software, or others. However, some members noted that they don’t have access to or aren’t aware of the full range of resources available. One cited example was Antidote. The member resources site on SharePoint, which serves as a repository of member supports, should be kept up to date and all members should know how to access this site to further their plain language skills. These tools, supports and the SharePoint site should be included in new member learning programs.

Recommendation # 2

Make clearer the appeal outcome right from the outset of the decision. Two possible approaches could be:

- State the outcome earlier, such as in the cover letter. The cover letter of decisions that refuse leave or summarily dismiss already state the decision, and this practice could extend to merit decisions.

- Consider alternatives to the terms “claimant”, “appellant”, and “respondent” by using, for example, the claimant’s initials to make it easier for people to find themselves in the decision.

Recommendation # 3

Claimants both successful and unsuccessful expressed a desire for clarity regarding what happens after the decision. Although the decision cover letter sets out such information, consider ways to reinforce the messages found there.

Recommendation # 4

Members could be reminded of the need to help readers with headings and sub-headings that are clear, content-specific, and useful to guide the reader through complex material.

Recommendation # 5

Members could be encouraged to continue to minimize the use of both legal and medical jargon and, when using jargon, to explain or paraphrase their meaning, as appropriate.

Recommendation # 6

Members could be reminded to keep sentences short by breaking up ideas and making each one the subject of its own sentence.

Recommendation # 7

This evaluation reviewed several exemplary decisions in English and French. These decisions could be leveraged for teaching purposes in new member learning sessions. As research participants for this study, the members’ consent would be necessary before release.

Appendix A: Interview guide of members

Name of member:

Name of interviewer:

Date of interview:

Mode (telephone, Teams, Zoom):

Introduction

Since 2018, the Social Security Tribunal has provided its members with supports to promote plain language in decision-writing. Most recently in 2021, the SST produced and released a style guide, self-editing tips, and decision templates.

The SST is now conducting an evaluation of plain language decision-writing in the Tribunal. The purpose is to assess the trends and patterns in decision-writing after the last rollout of supports to members. The evaluation seeks to understand members’ perceived gaps, needs and reservations with respect to further entrenching plain language in decision-writing.

The purpose of this interview is to obtain your feedback on plain language decision-writing, the supports available to you, and your professional development needs.

The information gathered will be summarized in aggregate form. Interview notes will not be shared outside of the Accountability unit. With your permission, we will record this interview in Teams. Teams is designed to make the recording available only to us three who have joined this meeting.

Questions

- What training and resources related to plain language decision-writing have you accessed?

- How effective were these training and resources in helping you improve your plain language decision-writing skills?

- To what extent are plain language writing skills valuable to your work?

- To what extent would you say that your decisions are now easier to ready to laypersons?

- What makes it challenging to apply plain language strategies in your decision-writing?

- What additional training or support would you like from the Tribunal?

- Do you have anything else to add?

Appendix B: Survey to clients

Survey administration and accuracy

The Secretariat to the SST sent an email invitation to all parties without a paid representative and who had received a decision between February 1, 2022 and May 31, 2022 to complete the survey online. Parties with a paid representative were screened out, as members may have written the decision for a legal professional in mind. Of the 1,140 clients contacted, 155 responded, or 14%. The 155 decisions were written by 43 different members. The results are considered statistically accurate within plus or minus 7 percent, 19 times out of 20. Although results presented above were stratified across key subgroups, the sample was not weighted due to the small sample size.

| 1. When you first read the decision, was it clear right away if you won or lost the appeal? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 62% | 96 |

| Somewhat | 19% | 30 |

| No | 19% | 29 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 155 |

| 2. How complicated was the wording? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Not Complicated | 58% | 89 |

| Somewhat Complicated | 30% | 46 |

| Very Complicated | 12% | 19 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 154 |

| 3. How much of the decision did you read? | ||

|---|---|---|

| All of it | 87% | 135 |

| Most or some | 7% | 11 |

| Very little | 6% | 9 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 155 |

| 4. Did someone else help you to understand the decision? | ||

|---|---|---|

| No | 68% | 106 |

| Yes | 31% | 49 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 155 |

| 5. Overall, on a scale of 1 to 4, how clear and understandable was the decision? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Very clear and understandable | 51% | 79 |

| Somewhat clear and understandable | 30% | 46 |

| Somewhat not clear and understandable | 10% | 16 |

| Not at all clear and understandable | 8% | 13 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 154 |

| 6. What else could make decisions easier to read? (check as many as you want) | # of responses |

|---|---|

| Explain what will happen next | 23 |

| Spell out result | 25 |

| Use less technical terms | 13 |

| Make the decision shorter | 12 |

| Number of respondents = 65 | |

| 7. Educational attainment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Some elementary or High School | 5% | 8 |

| High School | 23% | 36 |

| College, Cégep, Trade School, Apprenticeship | 37% | 59 |

| University | 34% | 52 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 154 |

| 8. Respondent types | ||

|---|---|---|

| Claimant | 87% | 134 |

| Unpaid Representative | 8% | 12 |

| Added party | 3% | 4 |

| Other | 1% | 2 |

| Don't know | 1% | 2 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 155 |

| 9. First language | ||

|---|---|---|

| English | 71% | 110 |

| French | 16% | 24 |

| Other | 13% | 20 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 154 |

| 10. Division | ||

|---|---|---|

| General Division—Income Security | 21% | 32 |

| General Division—Employment Insurance | 68% | 106 |

| Appeal Division | 11% | 17 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 155 |

| 11. Appeal outcome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Successful | 61% | 95 |

| Unsuccessful | 37% | 58 |

| Grand Total | 100% | 154 |

Percentages above may not add up to 100 due to rounding

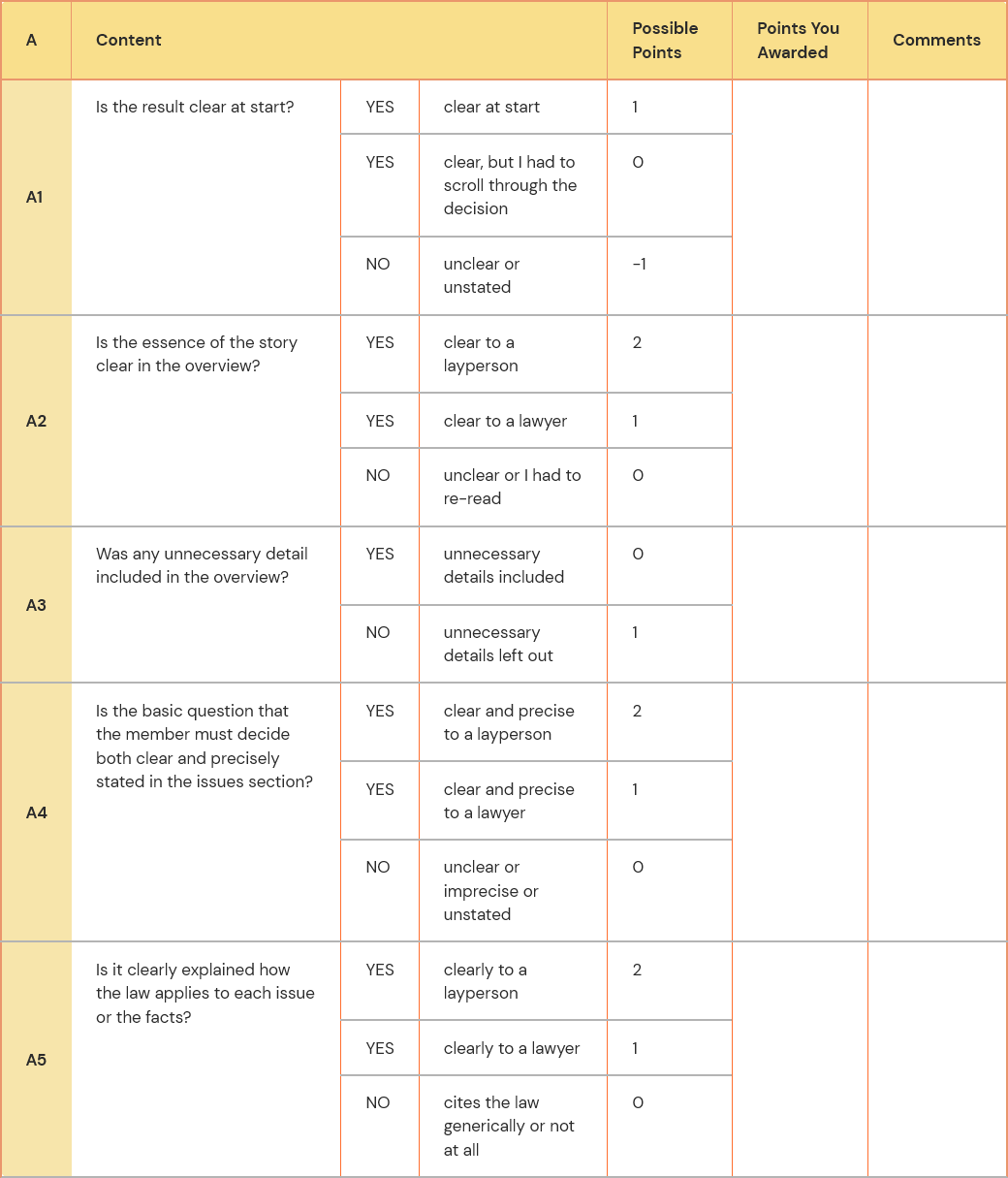

Appendix C: Readability scorecard

Text Version

Scorecard A

Question A1: Is the result clear at start? Possible answers: Yes, clear at start; Yes, clear, but I had to scroll through the decision; No, unclear or unstated

Question A2: Is the essence of the story clear in the overview? Possible answers: Yes, clear to a layperson; Yes, clear to a lawyer; No, unclear or I had to re-read

Question A3: Was any unnecessary detail included in the overview? Possible answers: Yes, unnecessary details included; No, unnecessary details left out

Question A4: Is the basic question that the member must decide both clear and precisely stated in the issues section? Possible answers: Yes, clear and precise to a layperson; Yes, clear and precise to a lawyer; No, unclear or imprecise or unstated

Question A5: Is it clearly explained how the law applies to each issue or the facts? Possible answers: Yes, clearly to a layperson; Yes, clearly to a lawyer; No, cites the law generically or not at all

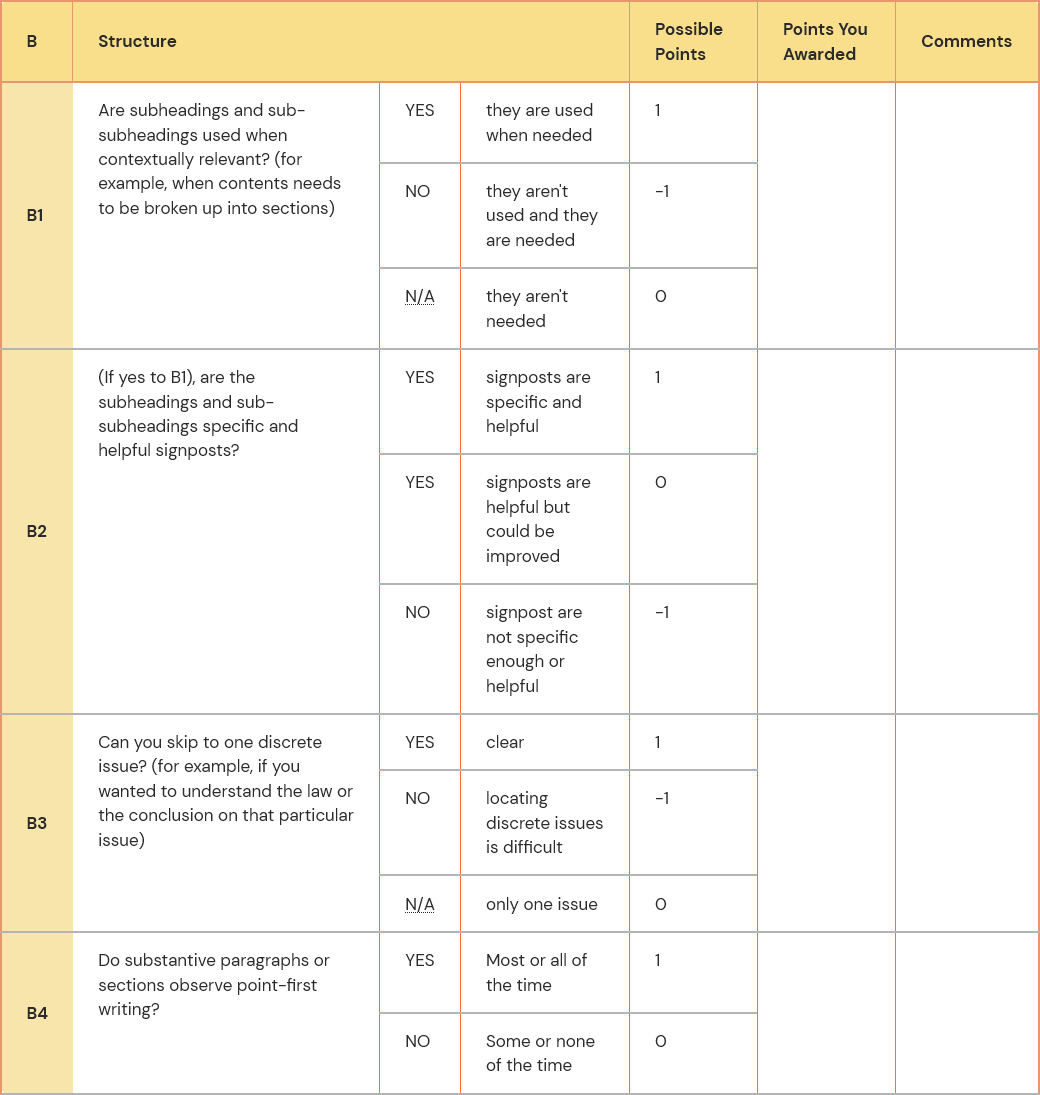

Text Version

Scorecard B

Question B1: Are subheadings and sub-subheadings used when contextually relevant? (for example, when contents needs to be broken up into sections) Possible answers: Yes, they are used when needed; No, they aren't used and they are needed; N/A, they aren't needed

Question B2: (If yes to B1), are the subheadings and sub-subheadings specific and helpful signposts? Possible answers: Yes, signposts are specific and helpful; Yes, signposts are helpful but could be improved; No, signpost are not specific enough or helpful

Question B3: Can you skip to one discrete issue? (for example, if you wanted to understand the law or the conclusion on that particular issue) Possible answers: Yes, clear; No, locating discrete issues is difficult; N/A, only one issue

Question B4: Do substantive paragraphs or sections observe point-first writing? Possible answers: Yes, most or all of the time; No, Some or none of the time

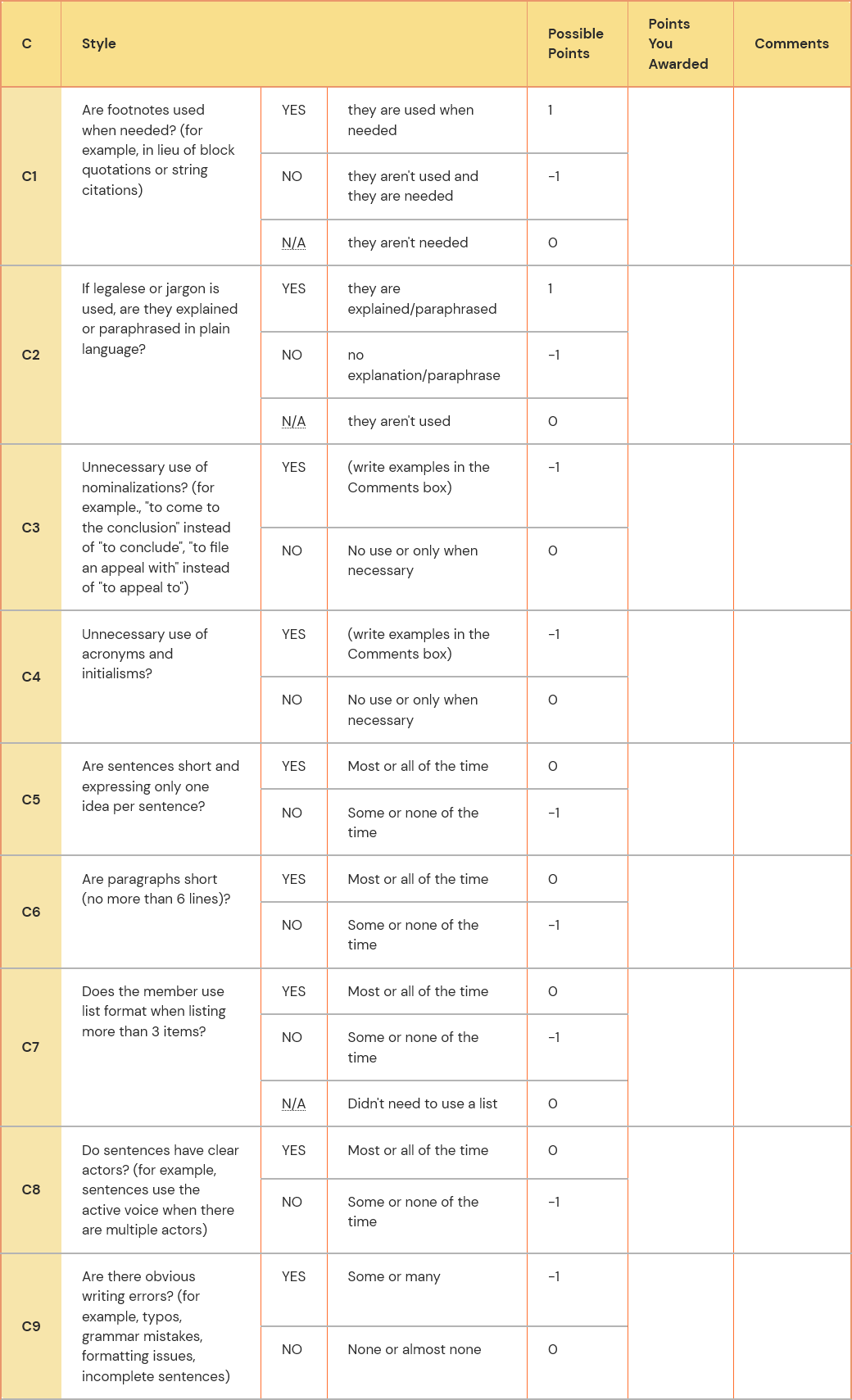

Text Version

Scorecard C

Question C1: Are footnotes used when needed? (for example, in lieu of block quotations or string citations) Possible answers: Yes, they are used when needed; No, they aren't used and they are needed; N/A, they aren't needed

Question C2: If legalese or jargon is used, are they explained or paraphrased in plain language? Possible answers: Yes, they are explained/paraphrased; No, no explanation/paraphrase; N/A, they aren't used

Question C3: Unnecessary use of nominalizations? (for example., "to come to the conclusion" instead of "to conclude", "to file an appeal with" instead of "to appeal to") Possible answers: Yes (write examples in the Comments box); No, no use or only when necessary

Question C4: Unnecessary use of acronyms and initialisms? Possible answers: Yes (write examples in the Comments box); No, no use or only when necessary

Question C5: Are sentences short and expressing only one idea per sentence? Possible answers: Yes, most or all of the time; No, some or none of the time

Question C6: Are paragraphs short (no more than 6 lines)? Possible answers: Yes, most or all of the time; No, some or none of the time

Question C7: Does the member use list format when listing more than 3 items? Possible answers: Yes, most or all of the time; No, some or none of the time; N/A, didn't need to use a list

Question C8: Do sentences have clear actors? (for example, sentences use the active voice when there are multiple actors) Possible answers: Yes, most or all of the time; No, some or none of the time

Question C9: Are there obvious writing errors? (for example, typos, grammar mistakes, formatting issues, incomplete sentences) Possible answers: Yes, some or many; No, none or almost none